The Jazztet At Birdhouse

Released 1961

Recording and Session Information

Art Farmer, trumpet; Tom McIntosh, trombone; Benny Golson, tenor saxophone; Cedar Walton, piano; Tommy Williams, bass; Albert "Tootie" Heath, drums

Live "Birdhouse", Chicago, IL, May 15, 1961

11208 Junction

11209 Farmer's market

11210 Darn that dream

11211 Shutterbug

11212 'Round midnight

11213 A November afternoon

Track Listing

| Junction | B. Golson | May 1961 |

| Farmer's Market | A. Farmer | May 1961 |

| Darn That Dream | E. DeLange, J. V. Heusen | May 1961 |

| Shutterbug | J.J. Johnson | May 1961 |

| Round Midnight | B. Hanighen, C. Williams, T. Monk | May 1961 |

| November Afternoon | T. McIntosh | May 1961 |

Liner Notes

THIS is the fourth album by the Art Farmer-Benny Golson Jazztet, and it's happy I am that I can tell you in all truth it continues their record-breaking Argo cavalcade.How long it will go on the Lord only knows, but as for the present, they've once again come up with something new as well as another first-rate program of jazz music.

Not to keep you in suspense, but to tell the story from the start, the first record was set by Meet The Jazztet (Argo LP 664). Since this was the group's initial album it necessarily was something new. Even better, according to The Jazztet's manager, Kay Norton, is that the LP turned out to be a consistent good seller.

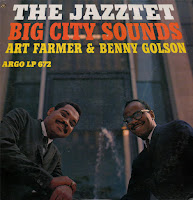

The second Jazztet album, Big City Sounds (Argo LP 672), presented a reorganized lineup, with only the leaders remaining from the original unit.

The unusual feature of the third album, The Jazztet And John Lewis (Argo LP 684), is the material: Six compositions by the internationally-famed musical director of the Modern Jazz Quartet which he arranged specifically for The Jazztet.

The Jazztet's newest album — the one you're holding as you read this — is the first ever made by the group during a public performance. It also marks Art Farmer's recording debut on the fluegelhorn.

The six extended numbers that comprise this set were taped a few months ago while The Jazztet was at the Birdhouse, a jazz club on Chicago's Near North Side. Farmer and Golson have a particular fondness for the club, not only because The Jazztet opened it about a year ago, but also because of the room's superior acoustics. Hence the suggestion that Argo tape the group during performance at the Birdhouse was quickly accepted.

So far as this observer is concerned, the decision was both wise and highly rewarding. Studio sessions can eliminate the occasional fluffs and clinkers to which even the best jazz instrumentalists are subject while in the throes of spontaneous creation, but at the same time such sessions lose the emotion-gripping quality that is instilled by a performance for paying customers. Evidences of this energizing situation are to be found here in the listeners' applause for soloists and the group, in occasional out-cries by the musicians, and in the music itself.

Before dealing with the individual selections, something about The Jazztet should be noted for the benefit of those still unacquainted with the group. The Jazztet was conceived in the summer of 1959 when Farmer and Golson, separately planning to organize their own combos, each broached this idea to the other. It soon became apparent that their aims were similar: Creation Of a group that would strike a musical balance between organization, as exemplified by fresh, thoughtful writing, and extemporization, the heart of jazz. That they have been eminently successful in steering a safe course between the Scylla of a "jamming band" and the Charybdis of an "arranger's band" is the firm belief of this writer.

The Music

Jünction, an easy rocker that evokes the Count, is a Golson composition and arrangement. Benny slips into the forefront smoothly and lightly to launch a flowing tenor solo that becomes assertive near its end. Farmer joins in with some clipped observations before proceeding to speak his piece, a somewhat fragmented discourse that has the rhythm section commenting.

Farmer's Market is Golson's arrangement of the composition that Art created some ten years ago and which received its most notable expositions in the late Wardell Gray's tenor solo and in the 1952 vocal written and recorded by Annie Ross. In the present version the tune is taken at racetrack tempo. There are cooking solos by both Benny and Art. Pianist Cedar Walton, who takes the spotlight after a drum break and stage-setting ensemble passage, contributes an exceptional solo that contains some notable phrasing and intriguing shifts of meter.

Darn That Dream, the only "pop" standard in the album, is a showcase for the Farmer fluegelhorn and proves that the months Art has devoted to this instrument were well spent. It is evident that he has accomplished the unusual feat of transferring his own wide, warm trumpet sound to the horn, a quality that adds to the effectiveness Of ballads such as this. The tender mood that Farmer creates and the beautiful coda with which he ends the piece further confirms the belief that he has few peers in this romantic realm.

Shutterbug is the J.J. Johnson tune and he arranged this uptempo version for The Jazztet. A staccato introduction heralds Farmer's solo during the course of which he demonstrates his fine control of sound as well as his ability to play hot. With the rhythm section stoking the fire to keep the pot bubbling, Golson moves in for a solo that exhibits his command of high-speed technique and, more importantly, his talent for improvisation. Drummer Albert Heath gets a brief solo before the minor.feeling number is concluded with a senerous ensemble.

'Round Midnight is the longest and, to this listener, the most rewarding number on the album. Golson's arrangement of Monk's lovely composition an The Jazztet's playing of it attain the group's aims to the fullest extent. The opening horn note and brief piano passage establish the mood, which is most movingly amplified by the succeeding segment that has a passage by fluegelhorn, a three-horn voicing, a brief, rhapsodic tenor interlude and another ensemble bit. Farmer introduces a new element with a trumpet solo which seems to hint that the sun will again be shining a few hours hence. The mood changes again as Golson comes on with a tenor solo that begins with a beautiful singing quality that gradually is transformed into a soul-wrenching cry. As the rhythm moves into a more propulsive groove, the sound of the tenor expands to climax its tale of loneliness. I believe this to be one of Benny's finest recorded solos. The arrangement makes further effective use Of the instruments before conduding its provocative story.

November Afternoon was written and arranged by trombonist Tom McIntosh. A delightful piece, it hints at a ballad as it begins but quickly shifts into a romping vein. While the number gives a fine display Of McIntosh's work, Farmer and Golson are not neglected. Here too, as throughout the album, the support of bassist Tommy Williams, Walton and Heath is of high value.

Russ Wilson